The following notes on Restrictive Covenants, Easements, Roads and Adverse Possession were originally based on a presentation to the University of Melbourne’s undergraduate Property Law class. They provide a reasonably comprehensive overview of the law in relation to the construction, modification and removal of restrictive covenants in Victoria. The sections on easements, roads and adverse possession are not as detailed, but nonetheless might be of a good starting point for lay people.

Restrictive Covenants FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What is a restrictive covenant?

A restrictive covenant is a contract that runs with the land, that is negative in nature. More particularly, a restrictive covenant is an agreement creating an obligation which is negative or restrictive, forbidding the commission of some act. In its most common form it is a contract between neighbouring land owners by which the covenantee determined to maintain the value of a parcel of land or to preserve its enjoyment, acquires a right to restrain the other party, namely the covenantor, from using the land in a certain way: Fitt v Luxury Developments Pty Ltd (2000) VSC 258. The land subject to a restrictive covenant is known as the burdened land and the land with the corresponding ability to enforce the covenant is known as the benefited land.

How do I know if land is burdened by a restrictive covenant

If a restrictive covenant burdens or runs with a parcel of land, it should be noted under the heading “Encumbrances, Caveats and Notices” on a certificate of title available from Landata. You can then search Landata again for the relevant covenant that is often contained within a Transfer of Land, or ask a title searching firm to do this for you. One such title searching firm is Feigl & Newell on (03) 9620 7022.

How do I know if land has the benefit of a restrictive covenant?

Typically, the extent of beneficiaries can be discerned from a careful reading of the words of the covenant itself, but this may require further title searches and a careful examination of the Parent Title. Some covenants purport to convey the benefit of a covenant to all land in a subdivision, which may not be legally effective, see Re Mack and the Conveyancing Act [1975] NSWLR 623. Before you become a party to proceedings concerning the modification or enforcement of a covenant, seek advice from a lawyer with experience in this area. Many people assume that because their land is located within an estate burdened by a network of similar covenants, they are necessarily a beneficiary to other comparable covenants, which may not be the case. See too, the section on Building Schemes, below.

How do I vary or modify a restrictive covenant?

There are several ways in which restrictive covenants can be varied or modified, but the two most common means are via a planning permit application to the local council or by application to the Supreme Court.

There is an initial appeal to applying for a permit to modify a covenant via the planning permit or Planning and Environment Act 1987 process, because it is seen to be cheaper and easier, but this appeal diminishes when one understands that all beneficiaries need to be notified (unless a pre-existing breach is being regularised) and for covenants created before 25 June 1991, only one genuine objection from a beneficiary is sufficient to bring the process to an abrupt halt.

For this reason, applications that might be seen as even slightly controversial, such as increasing the number of dwellings on a lot, routinely go straight to the Supreme Court. Most applications to the Supreme Court are successful as they proceed through the process without sustained objection, but the challenge here is to pitch your application at something a judge will be comfortable with, for the Courts have traditionally acted with caution when it comes to modifying restrictive covenants.

For more information about the various options for modifying or removing a restrictive covenant in Victoria see here.

How do I modify a covenant through the Supreme Court?

To modify a covenant through the Property Law Act 1958, or Supreme Court, process, an applicant will typically need a planning report prepared by a planner with experience in this area of law and an Originating Motion drafted by a solicitor. There are numerous other procedural requirements that invariably require the involvement of an experienced and competent lawyer.

Once the application is lodged with the Court, a hearing is convened at which directions for advertising is given by an Associate Judge. Typically the notification process will take eight to ten weeks before a further hearing is convened at which objections may be considered by the Court.

If no objectors appear to be heard, which is routinely the case, the Court will consider granting the relief sought, but a judge may still want to be convinced about the appropriateness of the application. If it is positively received, relief may be granted at that time. However, if the matter is contested, directions may be given for the exchange of evidence and submissions and the hearing may be listed some six months or so later for determination.

A detailed description of the process of modifying or removing a restrictive covenant in the Supreme Court is set out here along with a comprehensive collection of precedents.

How do I object to an application to vary a restrictive covenant?

An objection to vary a restrictive covenant does not need to take any particular form. However, it is useful to understand what the Court deems to be a relevant or persuasive reason to object against what is typically seen as being irrelevant or difficult to establish. A useful indication was given by Justice Cavanough in Prowse v Johnston who gave weight to objections that complained of loss of character, loss of privacy, the bulk of the proposed building, additional noise, traffic, parking and access issues and most importantly, that of precedent, that is, is this proposal the thin edge of the wedge?

An article setting out the process of objecting to a restrictive covenant in Victoria is set out here.

The Supreme Court published a guide for objectors in December 2017.

What is a building scheme?

Where a building scheme, or scheme of development is established, all purchasers and their assigns are bound by, and entitled to the benefit of, the restrictive covenant. However, notwithstanding the frequency with which they are discussed, in Victoria, they are not often established. The real difficulty in attempting to uphold a building scheme in this state is establishing that a purchaser of land was or should have been aware that a building scheme was in place prior to purchase and therefore ought to be bound by its terms. See Randell v Uhl [2019] VSC 668. An authority that helpfully sets the relevant principles is Vrakas v Mills [2006] VSC 463.

How to interpret a restrictive covenant

An article setting out some principles for the construction or interpretation of a restrictive covenant in Victoria is set out here.

Should I buy land subject to a restrictive covenant?

If the land is of no use to you unless the covenant is modified, it is probably unwise to buy it. The process of modifying a covenant is often too uncertain, too time consuming and too expensive to justify taking the risk. Covenants can cost as little as a few thousand dollars to modify if things go well. On the other hand, parties have spent close to half a million dollars to modify covenants without success. Equally, some modifications may be completed within weeks. Others may take years. Most applications to modify covenants receive little or no sustained opposition, others ignite well orchestrated and well resourced community campaigns. Any estimate as to prospects is just a well informed guess. If you’re not dissuaded, get a beneficiary report from Feigl and Newell and then find a lawyer with experience in the modification of restrictive covenants to give you an estimate of the likely opposition to change. You may be lucky and find there only a few beneficiaries who live some distance away.

How can I find a restrictive covenant lawyer?

The modification or removal of restrictive covenants is a specialised area of law and regularly done by only a handful of lawyers in Victoria. An article setting out a reliable means of finding a lawyer with experience in the jurisdiction is set out here.

Costs in an application to modify a restrictive covenant

An article summarising the principles in relation to orders of costs in s84/Supreme Court proceedings is set out here.

Representing yourself in an application to modify a restrictive covenant

Judges make every effort to accommodate self-represented litigants. The Supreme Court even has a self-represented litigant coordinator who may be able to provide you with some guidance.

Traditionally, the practice has been to set the matter down for a contested hearing in the normal manner, with the exchange of evidence and submissions. This can involve much time and a large amount of preparation. But more recently, the Supreme Court has facilitated self-represented litigants in covenant cases, by giving people an opportunity to present a short submission at the second return of the application, that is, immediately after advertising. In this way, litigants in person can put a short summary of their views to the judge, without becoming a party to the proceedings; without the need to prepare evidence or cross examine witnesses; and without the potential costs consequences of running a contested case to its conclusion. It must be remembered though, that this will occur in the course of a busy Court list and the judge’s capacity or preparedness to entertain detailed submissions will be limited. The Plaintiff also may elect to not press its case at this second return, and may ask the Court to set the case down on a future occasion, at which time the application can be heard and determined in a more considered manner.

Further, although there are cases in which the court has refused applications to modify covenants, even where there are no parties in opposition such as in Re: Jensen and in Re: Morihovitis, in practice, it is probably fair to say that a defendant has far lower prospects of success if they are not represented, and the plaintiff’s case is not thoroughly tested.

As mentioned above, the matters you wish to put before the Court are set out here.

Mediation and applications to modify restrictive covenants

An article explaining the role and utility of mediating covenant disputes in the Supreme Court is set out here.

How do I deal with a restrictive covenant that gives a discretion to a deregistered company?

An article setting out the process for dealing with a restrictive covenant that confers a discretion on a deregistered company is set out here.

A step by step guide to modifying a restrictive covenant under the Property Law Act 1958 with precedents

Originating motion in support of an application to modify or remove a restrictive covenant

If you are yet to decide which process to follow to modify or remove a restrictive covenant, you should read this article first. If you have already elected to pursue the Property Law Act 1958 or Supreme Court process, then the following discussion is an overview, along with some precedents you may wish to use. These are updated regularly.

To begin, when applying to remove or modify a covenant in the Supreme Court, an Originating Motion will need to be prepared, setting out the relief sought. Most applications will only need a simple Originating Motion such as this, this, this or this. More complex examples that incorporate applications for declarations can be found here, here, here and here.

In determining how to phrase the modification sought, you should seek the minimum change necessary to achieve your objectives. That is, if you are after a dual occupancy, seek to replace ‘one dwelling’ with ‘two dwellings’ or draft a variation to allow a particular form of development. Although a practice has been to vary covenants with the addition of the following words “… but this covenant will not prohibit the construction of any development generally in accordance with the development described in the plans prepared by ABC Architects dated 1 July 2016 numbered A00 to A30”, this technique known as the ‘proviso’ has recently fallen out of favour with the Court because it means attaching plans to an instrument of transfer that may sit in the Office of Titles for decades to come. For this reason, orders that incorporate a simple building envelope are preferred. The broader point, however, is that if you ask for removal of the covenant and you don’t actually need it, you may attract unwarranted opposition. Moreover, the Court is increasingly unwilling to allow the complete removal of anything but obsolete covenants.

No summons is required at this time given that the first hearing will ordinarily be ex parte.

While the schedules of parties may have been removed from the attached examples, such a schedule is ordinarily not added until after the first return of the application, for the identity of the Defendants is not likely to be known until that time.

Overarching Obligations Certification and Proper Basis Certification should also be provided.

The Court will also want an application form completed.

A helpful Guide for Practitioners has also been prepared by the Supreme Court. This provides a checklist for applications and some draft precedents. This version was updated by the Court in December 2016, but to be prudent, download the latest version from the Supreme Court website. As at March 2018, it is understood that a review is presently underway.

Affidavit in support of and in opposition to an application to remove a single dwelling covenant

Current practice is to include an affidavit from the Plaintiff setting out the intended use and development for the property. If the land is to be sold, that should be disclosed and the Court given a realistic understanding as to how the land might be used or developed. An example of a Plaintiff’s affidavit can be found here. Traditionally, solicitors would give this information to the Court on instructions, but the emerging best practice is to hear from the applicant directly.

The Court will also want to know whether there has been previous applications to modify or remove a restrictive covenant on the land.

If the land is under contract, full details of that should be out too. Indeed, there is an argument to suggest that the application should be made under the name of the owner, even if the land is under contract.

The objective is to provide the Court with reliable information about the covenant; its purpose; the identification of land with the benefit of the covenant; and any relevant circumstances surrounding the application. Ensure you have an up-to-date certificate of title for the land and that the application is made on behalf of that party or those parties.

If relying on a map showing the location of beneficiaries, ensure the map is clear and legible and accurately reflects the location of beneficiaries.

The quickest and most cost-effective means of establishing who has the benefit and the burden of the relevant covenant is to call a professional title searching service such as Feigl and Newell on (03) 9629 3011. Dinah Newell should be able to provide you with a colour-coded cadastral plan such as this. However, you should double-check any advice you receive to identify transcription or other errors. Mistakes made at this point of the process can be expensive to fix later on.

Evidence in support and in opposition to the modification of a covenant

Once you have the above information, you can provide it to a town planner for the preparation of a planning report. Two further examples can be found here and here. This version was in support of an application to modify a covenant restricting the height of a dwelling and was praised by the Court for its clarity.

A letter instructing a town planner in a s84 application can be found here. If you want the names of planners to prepare evidence in support of (or against) an application to modify or remove a covenant, find someone who has given evidence in a contested s84 application. You can look through Supreme Court cases in relation to restrictive covenants here. Unfortunately, all too often, planners approach the task as if it were a common or garden planning application in VCAT relying on principles of public policy rather than analysing impacts on proprietary rights. This evidence will almost certainly be useless. Just as importantly, a ‘cheap’ planning report may end up becoming expensive once it becomes clear how much additional work it will create for the lawyers to fix it up. Applicants are reminded that the Supreme Court is not the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal where the tribunal member can patch up evidentiary gaps with their own knowledge and experience. In the Court, judges are confined to the evidence and if your planner does not adequately address the merits of the application in his or her written evidence, at trial, any significant omissions can be fatal.

A planning report should include photographs of the neighbourhood so the Court can gain a clear understanding of the context in which the application is being made.

It should also identify land within the parent title that has been varied since the time of the original subdivision, whether this is by order of the Court, planning permission or simply a breach that has gone unchallenged. Evidence demonstrating how that change has occurred, should be annexed to the planning report when available. Often this will be the pivotal evidence in the hearing and it must be done with precision.

Applicants are sometimes keen to lodge the application without planning evidence to save costs or time, but this risks the application being dismissed for being improperly supported. Any planning evidence should be before the Court at or before the first return of the application.

In some cases, lay evidence may be sufficient, at least in opposition to a modification or removal application. For instance, in Gardencity v Grech, the defendants were successful despite the absence of any expert evidence, for the Court found the plaintiff had failed to prove the absence of substantial injury. Evidence from the defendants in that case can be found here, here and here. An example of an expert report in support of an application to oppose a modification can be found here.

For a separate discussion about what to include in an objection, look here.

The first return of the application

At the first hearing of an application, which is usually done ex parte, the Court is likely to make further orders, similar to the following for a sign to be placed on the land and for direct notice to be given to the closest beneficiaries. This raises a tactical question for applicants for it may be prudent to suggest to the Court that all beneficiaries be notified directly rather risk attracting the attention of non-beneficiaries via a sign on the land.

On the other hand, the Court has been known to be content with simply a sign on the land and no direct notification if there are no nearby beneficiaries.

The Court now also directs applicants to notify the beneficiary at the address indicated on title and at the street address, if different.

As always, practitioners should attend the Court with draft orders, preferably forwarded to the Court a few days beforehand. The Court is now directing the attachment of Information for Objectors to the draft orders. An example can be found here.

The normal standards expected of practitioners in ex parte applications apply, and you should disclose to the Court any necessary countervailing facts even if they are not helpful to your case. For instance, if your client is running a simultaneous application to modify a covenant elsewhere (which isn’t a good idea), the Court will want to know about it.

The second return–if the application is opposed

Once advertising has been carried out, an affidavit should be prepared that describes the process undertaken, the nature of responses received and whether any beneficiaries objected. This is a short example and a more comprehensive example. Leave sufficient time to complete this as it may be time consuming.

A sample letter sent should be included in the affidavit–not a copy of each letter sent.

In answering queries from third parties, including beneficiaries, avoid giving advice about who has the benefit of the covenant. Inquirers need to make their own investigations about their entitlement to participate in the proceedings and the answer is not always clear. Record details of all phone calls and emails as a summary should also be included in the affidavit of compliance.

The Court may then make orders providing for the further provision of evidence and the listing of the matter for hearing. Two examples can be found here and here. The schedule of parties may have been removed.

Increasingly, covenant cases are being set down for mediation.

The second return–if the application is not opposed

If no person seeks to become a Defendant, draft orders should be provided to the Court along with an affidavit to that effect (see examples above). Try to get the papers to the court three or four days in advance of the directions hearing so that the judge has time to read them before the hearing. An example can be found here.

Significantly, you may find that despite the absence of any defendants, you may still need to make out your argument for modification on the basis of the evidence provided. For instance, in Re Jensen, and Re: Morihovitis the Court refused relief despite the absence of any objectors.

A written outline of argument setting out why the variation or removal of the covenant should be provided to the Court, preferably in advance of the hearing. Two examples can be found here and here.

Submissions in support and in opposition to application to modify a single dwelling covenant

If the matter runs to a contested hearing, you will need to prepare a more comprehensive outline of argument. Submissions in support of a modification application can be found here: from Wong v McConville (opening); Wong (closing) and Re: Milbex. Submissions in opposition to a modification application can be found here from Re Pivotel; Suhr v Michelmore; and Prowse v Johnstone; and Re: Morrison.

To improve your client’s costs position in the litigation, a Calderbank letter or offer of compromise may be appropriate to disturb the defendants’ presumption that their costs will be reimbursed by the Plaintiff at the conclusion of the proceedings, irrespective of the outcome. A Calderbank letter needs to be drafted with precision and according to established principles if it is to be effective. Examples can be provided upon request.

Needless to say, all applications are different and great care should be taken to ensure that the relevant matters are placed before the Court.

townsend@vicbar.com.au

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation.

Removing or modifying a restrictive covenant in Victoria

This article briefly describes a number of ways to modify or remove a restrictive covenant in Victoria, namely:

– by planning permit pursuant to clause 52.02 of a planning scheme–mostly useful for a deadwood or non-contentious covenant;[1]

– the making of orders pursuant to s84 of the Property Law Act 1958 (PLA)–the most common route for potentially contentious applications;

– by amending the relevant planning scheme–useful where there is considerable support for the proposed change at the municipal or state level;

– by consent–useful where there is a small number of beneficiaries and/or good relations amongst beneficiaries; and

– at the direction of the Registrar of Titles–useful where the covenant might be said to be personal or where the benefit of the covenant fails to pass.

For completeness, there has also been at least one instance, where the Court has been prepared to amend a restrictive covenant under s103(1) of the Transfer of Land Act 1958, where the Court concluded there had been a common mistake made by the parties to a transfer of land in the expression of a restrictive covenant.

The planning permit process

For what might be described as “deadwood” covenants, an application may be made for a planning permit to remove or modify a covenant pursuant to clause 52.02 of the relevant planning scheme.

However, the operation of s60(5) of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 (PEA) means that where there is a real prospect of genuine opposition, this avenue is to be avoided. Section 60(5) provides:

The responsible authority must not grant a permit which allows the removal or variation of a restriction … unless it is satisfied that—

(a) the owner of any land benefited by the restriction … will be unlikely to suffer any detriment of any kind (including any perceived detriment) as a consequence of the removal or variation of the restriction;

As described by DP Gibson of the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) in Hill v Campaspe SC [2011] VCAT 949 this is “a high barrier that prevents a large proportion of proposals.” For covenants created on or after 25 June 1991, a less restrictive test applies.[3] Hill v Campaspe was recently applied in Dacre v Yarra Ranges SC [2015] VCAT 1453.

A further disincentive to rely on this provision is the need to notify all, rather than the closest beneficiaries of the application.[4]

Interestingly, there is a provision that allows the circumvention of the onerous advertising provisions in the PEA where the breach has been in existence for two years or more. Section 47(2) of the PEA provides:

(2) Sections 52 and 55 do not apply to an application for a permit to remove a restriction (within the meaning of the Subdivision Act 1988) over land if the land has been used or developed for more than 2 years before the date of the application in a manner which would have been lawful under this Act but for the existence of the restriction.

Section 52 of the Act deals with advertising of applications for permits to potentially affected third parties and section 55 deals with referral to bodies such as DELWP, Telstra, VicRoads and so on.

In Hill v Campaspe SC [2004] VCAT 1399, the Tribunal explained:

26 My conclusion is that if part of a covenant is breached, and the breach continues for 2 years without any action on the part of those having the benefit of the covenant, it is reasonable that no notice should be given of an application to vary by removal part of the covenant of which there is a breach. But this exemption from notice pursuant to section 47(2) of the Act should not extend to the removal of any aspect of a covenant of which there is no breach.

Although the proper interpretation of this provision is not free from doubt, this decision suggests that if a use or development has been in breach of a covenant for more than two years, a permit can be granted to remove or modify the covenant to regularise the use or development. If you rely on this provision, the relevant responsible authority under the Act should issue the permit to remove or amend the covenant without notifying other beneficiaries. However, as DP Gibson cautions, the power is limited, so any application should be judiciously drafted.

Section 84 of the Property Law Act 1958

Where some degree of opposition is expected from one or more beneficiaries, an application may be made to remove or modify the covenant pursuant to s84(1) of the PLA.

S84(1) is currently structured as a series of threshold tests to be satisfied before the court’s discretion to exercise the power is enlivened. The two most commonly relied upon are ss84(1)(a) and (c):

(1) The Court shall have power … to discharge or modify any such restriction (subject or not to the payment by the applicant of compensation to any person suffering loss in consequence of the order) upon being satisfied:

(a) that by reason of changes in the character of the property or the neighbourhood or other circumstances of the case which the Court deems material the restriction ought to be deemed obsolete or that the continued existence thereof would impede the reasonable user of the land without securing practical benefits to other persons or (as the case may be) would unless modified so impede such user; or …

(c) that the proposed discharge or modification will not substantially injure the persons entitled to the benefit of the restriction…

An application under s84(1) usually involves the filing of an Originating Motion and Summons for Relief with the Supreme Court. This application should be accompanied by planning or other evidence in support of the application for modification or removal.

This is returnable before an Associate Judge who may inquire as to the nature and location of beneficiaries before determining the extent of advertising—often a combination of letters to the closest beneficiaries and the posting of a sign on the land.

Orders may then be made for the return of the summons at a future directions hearing at which objectors may attend.[5]

A surprising number of applications attract no objections. Upon being satisfied that this is the case, the Court may grant the application.

Alternatively, objections may be received and/or objectors may attend court on the return.

If a mutually acceptable agreement on the application cannot be reached with the objectors, orders may be made for the exchange of further evidence before the matter is listed for mediation and/or final hearing.

Historically, the courts have taken a conservative approach to applications for the removal or modification of restrictive covenants. In the often cited words of Farwell J in Re Henderson’s Conveyance:

… I do not view this section of the Act as designed to enable a person to expropriate the private rights of another purely for his own profit. I am not suggesting that there may not be cases where it would be right to remove or modify a restriction against the will of the person who has the benefit of that restriction, either with or without compensation, in a case where it seems necessary to do so because it prevents in some way the proper development of the neighbouring property, or for some such reason of that kind; but in my judgment this section of the Act was not designed, at any rate prima facie, to enable one owner to get a benefit by being freed from the restrictions imposed upon his property in favour of a neighbouring owner, merely because, in the view of the person who desires the restriction to go, it would make his property more enjoyable or more convenient for his own private purposes.[6]

However, in recent times, the Court has been more prepared to agree to modification applications based on s84(1)(c) of the Property Law Act 1958. See Wong v McConville & Ors and Maclurkin v Searle.

The practical challenge is to reassure the court about the likely impacts of the proposed development scheme, while allowing sufficient flexibility in the subsequent town planning permit application process.

As Morris J explained in Stanhill:

… the lack of specific plans makes it more difficult for the plaintiff to discharge the onus of showing that a modification of a restriction will not substantially injure persons entitled to the benefit of the restriction.[16]

In view of this judicial need for certainty, or at least reassurance based on the ability to consider the detail of a development proposal, it would be sensible to allow the grant of a planning permit conditional upon the subsequent removal or variation of the subject covenant, but this possibility was ruled out by VCAT in Design 2u v Glen Eira CC[17]. In that case, DP Gibson held:

5 … I find that unless there is a prior or simultaneous grant of a permit or decision to grant a permit to allow the removal of variation of the covenant, a permit cannot be granted by either the responsible authority or the Tribunal if the grant of a permit would authorise anything which would result in a breach of the covenant. I find that as the grant of a permit in this particular case would result in a breach of the covenant affecting the subject land, the application for review must fail and should therefore be dismissed.

Regrettably, the Victorian Government elected to not remove this obstruction in its Response To The Key Findings Of The Initial Report of the Victorian Planning System Ministerial Advisory Committee.[18]

Applicants now need to substantially reduce the scope of development schemes in anticipation of a worst-case assessment by VCAT or simply articulate building envelopes into which future applications for planning permission may subsequently be contained.

Alternatively, for modest variations to covenants there is some scope to rely on the planning system as a means of ensuring that substantial injury would not result from the variation. This recently occurred in Hermez v Karahan [2012] VSC 443 when Associate Justice Daly held:

4 … in respect of the relevance of town planning principles in determining whether an applicant has established a ground for removal or modification of a restrictive covenant, Cavanough J agreed with the general principle laid down by the authorities that the desirability or otherwise of a proposed development, taking into account such considerations was not part of the Court’s function. However, his Honour was prepared to assume, without finally deciding the matter, that the existence of statutory planning provisions aimed at protecting the amenity of neighbours might be relevant for assessing substantial injury. For the purposes of this application, I am also prepared to assume that planning and building regulations governing building size and height, set backs, and allowable overshadowing and overlooking are relevant to assessing whether modifying the covenant would cause substantial injury.

Significantly, the court in Hermez allowed a variation of the covenant to replace the reference to “one dwelling” with “two dwellings” and didn’t confine the applicant to building two dwellings generally in accordance with a given set of plans.

Notwithstanding these matters, it would be a mistake to frame an application under s84(1)(c) solely on town planning concepts of amenity. For instance, in Fraser v Di Paolo[19] Coghlan J reviewed a number of authorities before observing: “These decisions were made more than 30 years ago but they do give an insight into the importance of the rights which go with a covenant beyond town planning rights.” In other words, substantial injury may occur merely through the diminution of proprietary rights, particularly if the decision may set a precedent.

The importance of costs in s84 applications

Potential applicants should be familiar with the cost implications of Re: Withers[20] that:

… unless the objections taken are frivolous, an objector in a proper case should not have to bear the bitter burden of his own costs when all he has been doing is seeking to maintain the continuance of a privilege which by law is his.

Re Withers was applied by Justice Morris in Stanhill v Jackon[21] who noted:

The principle set out in Re Withers is consistent with other decisions of the Court, such as that by Gillard J in Re Markin[22], Lush J in Re Shelford Church of England Girls’ Grammar School[23] and McGarvie J in Re Ulman.[24] In my opinion, it is a sound principle.

When acting for objectors, this rule may be of corresponding significance.

The combined permit/amendment process

Interestingly, the least-used means of removing or amending a covenant is also that arguably capable of delivering the most ambitious proposals, namely amending the planning scheme to remove or amend a covenant.[25]

In this process, the assessment is made according to ordinary planning principles:[26]

In the Mornington Peninsula C46 Panel Report, Member Ball explained:

First, the Panel should be satisfied that the Amendment would further the objectives of planning in Victoria. …

Second, the Panel should consider the interests of affected parties, including the beneficiaries of the covenant. It may be a wise precaution in some instances to direct the Council to engage a lawyer to ensure that the beneficiaries have been correctly identified and notified.

Third, the Panel should consider whether the removal or variation of the covenant would enable a use or development that complies with the planning scheme.

Finally, the Panel should balance conflicting policy objectives in favour of net community benefit and sustainable development. If the Panel concludes that there will be a net community benefit and sustainable development it should recommend the variation or removal of the covenant.[27]

Here an applicant runs an entirely different risk, for while the planning system might eschew Farwell J’s disdain for profitable property ventures, to succeed, an application will need the support of the local council and the relevant Minister at the time the amendment is both prepared and adopted. In the worst case, the period between these two events may be many months and punctuated by Council elections thus adding a political wildcard into an already unpredictable process.

An example of this process being successfully employed was the recent approval of a Place of Assembly (museum) at 217 And 219 Cotham Road, Kew as part of Amendment C143 to the Boroondara Planning Scheme. The proposal involved the conversion of two dwellings into a contemporary museum with liquor licence and few on-site parking spaces, contrary to a restrictive covenant that prevented the use of the land for anything other than dwellings. Arguably, there would have been no prospect that such an ambitious project would have been approved under s84 of the Property Law Act 1958, but the project received Council backing at both ends of the process and a highly favourable planning panel report.[28]

Removing or modifying a covenant by consent

A restrictive covenant can be removed or modified by consent. Section 88(1AC) of the Transfer of Land Act 1958 provides:

A recording on a folio of a restrictive covenant that was created or authorised in any way other than by—

(a) a plan of subdivision or consolidation; or

(b) a planning scheme or permit under the Planning and Environment Act 1987—

may be deleted or amended by the Registrar if the restrictive covenant is released or varied by—

…

(d) the agreement of all of the registered proprietors of all land affected by the covenant; …

If the proposed modification or removal is not controversial and/or the number of beneficiaries is not large, this may be the most efficient means of proceeding.

Removing a covenant at the direction of the Registrar of Titles

Finally, a covenant may be removed at the direction of the Registrar of Titles pursuant to s106(1)(c) of the Transfer of Land Act 1958. This provides:

(1) The Registrar—

(c) if it is proved to his satisfaction that any encumbrance recorded in the Register has been fully satisfied extinguished or otherwise determined and no longer affects the land, may make a recording to that effect in the Register;

This provision can be used for covenants that do not define the land to which the benefit is affixed or where the benefit of the covenant might be said to have not passed to subsequent successors or transferees. Covenants of this nature were discussed in Prowse v Johnstone [No. 2] [2015] VSC 621 at [62].

Download a .pdf of this article.

Matthew Townsend

Owen Dixon Chambers

http://www.vicbar.com.au/profile?3183

townsend@vicbar.com.au (04) 1122 0277

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation.

[1] “A permit is required before a person proceeds: – Under s23 of the Subdivision Act 1988 to create, vary or remove an easement or restriction or vary or remove a condition in the nature of an easement in a Crown grant.”

[2] [2011] VCAT 949 at [65]

[3] PEA s60(2): … must not grant a permit which allows the removal or variation of a restriction unless … the owner of any land benefited by the restriction … will be unlikely to suffer “a) financial loss; or b) loss of amenity; or c) loss arising from change to the character of the neighbourhood; or d) any other material detriment—as a consequence of the removal or variation of the restriction.”

[4] PEA s52(1)(cb).

[5] See R52.09 of the Supreme Court (General Civil Procedure) Rules 2005.

[6] [1940] Ch 835 at 846

[7] [2005] VSC 169; (2005) 12 VR 224, 231

[8] [2005] VSC 169; (2005) 12 VR 224, 231 [13], 239 [41]-[42]

[9] Per Daly AJ in Grant v Preece [2012] VSC 55 at [55]

[10] [2006] VSC 298

[11] [2007] VSC 426

[12] [2011] VSC 346

[13] [2008] VSC 281 at [48]

[14] (2007) 81 ALJ 68 at 71

[15] [2012] VSC 4

[16] [69]

[17] [2010] VCAT 1865

[18] Response to Committee Finding 26

[19] [2008] VSC 117 at [42]

[20] [1970] VR 319-320 at 320

[21] [2005] VSC 355

[22] [1966] VR 494.

[23] Unreported, 6 June 1967.

[24] (1985) VConVR 54-178.

[25] See Division 5 of the PEA “Combined permit and amendment process” or the use of site specific controls pursuant to clause 52.03 as occurred in Amendment C143 to the Boroondara Planning Scheme.

[26] M.A. Zeltoff Pty Ltd v Stonnington City Council [1999] VSC 270

[27] Amendment C46 to the Mornington Peninsula Planning Scheme at 25. Applied by the panels considering amendments C23 to the Stonnington Planning Scheme; C72 to the Manningham Planning Scheme; and C137 to the Mornington Peninsula Planning Scheme.

[28] http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/vic/PPV/2012/5.html?stem=0&synonyms=0&query=Amendment%20C143%20to%20the%20Boroondara%20Planning%20Scheme

[29] Easements and Covenants, Final Report #22; Recommendation 43.

Court of Appeal confirms the operation of prescriptive easements in Victoria

In Les Denny v Delma Valmorbida [2025] VSCA 319, the Court of Appeal upheld the decision of Justice Gorton in Delma Valmorbida v Les Denny [2023] VSC 680, to confirm the operation of easements by prescription in Victoria (or rights of long user).

The Court of Appeal concluded that at general law, an easement can arise based on 20 or more years of use, despite changes in ownership of the relevant land during the period of use.

Further, it held that:

- section 42(2) of the Transfer of Land Act 1958 (Vic) creates a number of exceptions to indefeasibility in respect of several ‘paramount interests’, including unregistered easements ‘howsoever acquired’.

- while there is an obvious tension between the policy of certainty of registered title and the express preservation of certain unregistered interests in land, the legislative history strongly supports a conclusion that the legislature has deliberately chosen to allow prescriptive easements acquired by long use as an exception to indefeasibility of title under the Transfer of Land Act; and

- unless and until Parliament amends the Transfer of Land Act to limit or remove the exception for unregistered easements in s 42(2)(d), the Court must give effect to the exception, despite the potential for it to operate unfairly.

See Les Denny v Delma Valmorbida [2025] VSCA 319:

Supreme Court explains when acquiescence is established in the event of a breach of a restrictive covenant

The Supreme Court has allowed the variation of a restrictive covenant in Lysterfield notwithstanding that the impacts of a new dwelling built in breach of the restriction would be “intrusive and oppressive.”

The Court found that the beneficiaries’ failure to act decisively when visited with the scale of the breach of the covenant was inexplicable.

“207 Even more baffling was the Perrys’ failure to make any further protest, or take any further action once they returned from Darwin in late September 2024. By this time, that the new dwelling breached the height restriction was unmistakeable. No further information was required for them to reach that conclusion. The roof sheeting had been installed, such that what was observed during the course of the view was visible to anyone from sometime in August 2024, and by the Perrys themselves from 29 September 2024. The construction of the new dwelling was advancing at some pace. But the Perrys took no steps to halt the construction of the new dwelling until five months after their return from Darwin.”

The Court found that this conduct amounted to acquiescence for the purposes of s84(1)(b) of the Property Law Act 1958 (Vic) and agreed to modify the covenant to allow the new dwelling and its pitched roof notwithstanding that that new dwelling would substantially impair the views from the Perrys’ living/dining room.

Before and after photos are at pages 4 and 14 in Jayasinghe v Perry [2025] VSC 751, below:

Planning reforms to overhaul Victoria’s law on restrictive covenants

UPDATE: The Legislative Council made amendments to the Bill on 9 December which have been referred back to the Legislative Assembly that is expected to next sit on 3 February 2026. If those amendments are accepted, the new amending Act will have a staged commencement whereby:

- The preliminary part of the Bill and the proposed new scheme for affordable housing contributions will commence on the day after the amending act receives royal assent; whereas

- The rest of the Act (implementing changes relevant to restrictive covenants) will come into force on:

- a day or days to be proclaimed; but

- if not in operation sooner, on 29 October 2027.

So importantly, the changes to the system for restrictive covenants is not expected to enter into force before 29 October 2027.

See: https://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/bills/planning-amendment-better-decisions-made-faster-bill-2025 A more detailed account of the Bill can be found here, in the section marked Reform: https://restrictive-covenants-victoria.com/2022/12/10/restrictive-covenants-in-victoria-theory-and-practice/

===================================

THE VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT has released the Planning Amendment (Better Decisions Made Faster) Bill 2025.

The proposed changes contain two significant changes to the regulation of restrictive covenants in Victoria.

FIRST, it is proposed that planning policy can be considered in the decision to remove or vary a restrictive covenant. The new section 60(2) will provide:

“Before deciding on a type 2 or 3 application which would allow the removal or variation of a restriction (within the meaning of the Subdivision Act 1988), the responsible authority must also consider the following—

(a) the impact of removing or varying the restriction on the material interests of the owner of any land benefited by the restriction (other than an owner who, before or after the making of the application for the permit but not more than 3 months before its making, has consented in writing to the grant of the

permit) in terms of—

(i) loss of amenity; and

(ii) loss arising from change of character to the neighbourhood; and

(iii) any other material detriment, other than financial loss, that may be suffered;

(b) the impact of the restriction on the ability to deliver—

(i) the objectives of planning in Victoria; and

(ii) any applicable State planning strategy, regional planning strategy or planning strategy for the area covered by the planning scheme; and

(iii) the objectives or purposes of the planning scheme;

(c) whether a matter that is the subject of the restriction to be removed or varied is also regulated by the planning scheme;

(d) if the removal or variation of the restriction is proposed in conjunction with an application for a permit for a use or development that would breach the restriction, for the purpose of considering a matter under paragraph (a), (b) or (c), whether that use or development is acceptable having regard to the matters set out in subsections (1), (1AA), (1A) and (1B) 15 (if relevant).“

The current wording of section 60(2) requires that the impacts on beneficiaries be resolved before planning policy can be considered. As Senior Member Wright QC explained in Waterfront Place Pty Ltd v Port Phillip CC [2014] VCAT 1558: “72. The Tribunal stated that in applying the tests set out in s. 60(2) it is not a question of balancing the loss suffered by a benefiting owner in each of the categories set out in paragraphs (a) to (d) against the planning benefits of removal or variation of the covenant. The tests must be applied in absolute terms. Consideration of the planning merits can occur only if the tests are satisfied and the discretion to grant a permit thereby enlivened. This Tribunal respectfully agrees.”

Section 60(5) is also proposed to be repealed. The existing section 60(5) of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 has been described as “a high barrier that prevents a large proportion of proposals”:

“(5) The responsible authority must not grant a permit which allows the removal or variation of a restriction referred to in subsection (4) unless it is satisfied that—

(a) the owner of any land benefited by the restriction (other than an owner who, before or after the making of the application for the permit but not more than three months before its making, has consented in writing to the grant of the permit) will be unlikely to suffer any detriment of any kind (including any perceived detriment) as a consequence of the removal or variation of the restriction; and

(b) if that owner has objected to the grant of the permit, the objection is vexatious or not made in good faith.“

Without any exaggeration, this provision means that someone could argue that the proposed modification or discharge of a covenant would make the beneficiaries’ curtains fade, and the decision maker would have to refuse the application. It has never been clear why this incredibly strict standard applies to pre-1991 covenants and a less strict standard applies to post 1991 covenants. In any event, this distinction is proposed to be brought to an end in the new Bill, as all covenants are proposed to be covered by the new s60(2), above.

SECOND, the Minister or responsible authority would be able to grant a planning permit that will breach a restrictive covenant. This removes a considerable burden from local councils that presently need to regularly seek legal advice on the proper construction of covenants to avoid granting a permit that may breach a restrictive covenant. As one senior government lawyer explained: “Councils are presently the gate keepers and arbiters of the private property law system. It’s incredibly unfair and generates an inordinate amount of work.”

But the covenants themselves will remain fully enforceable until they are removed or varied. This may lead to an increase in the number of injunction applications as people try to act on a planning permit and simply wait for one or more beneficiaries to stop them. The risks in doing so are high.

Prior to 2000, planning permits could be granted that would permit a breach of a restrictive covenant. For instance, in Luxury Developments v Banyule CC [1998] VCAT 1310 the Tribunal explained that its remit was exclusively the application of town planning controls and policies. It had no jurisdiction to consider the proprietary legal interests raised by the existence of a restrictive covenant. However, after the permit was granted and construction commenced, the residents of the Hartland Estate in Ivanhoe sought and were granted an injunction in the Supreme Court of Victoria to stop the development.

Luxury Developments subsequently went into liquidation, leaving the residents of the Hartlands Estate unable to recover their costs. Partly in response to this case, the Victorian Parliament passed the Planning and Environment (Restrictive Covenants) Act 2000, an Act that would prevent planning permits from being issued where they would breach a restrictive covenant. The proposed amendment will reverse the effect of that change to the Planning and Environment Act 1987.

IN CONCLUSION, the Supreme Court process may remain the preferred choice of jurisdiction for a number of restrictive covenant applications, such as: uncontroversial applications; applications for declarations; and applications not supported by state policy (such as an application to increase the height or number of storeys of a single dwelling)–appreciating that the Supreme Court tends to be much faster and ultimately less expensive than VCAT (and one that doesn’t ordinarily involve council planners or solicitors).

But for ambitious changes to restrictive covenants where multiple dwellings are proposed over the objections of beneficiaries, it may be that the new process creates a regulatory framework in which planning policy is given significant weight in a decision to amend or discharge a restrictive covenant. An example of this might be land along Wattletree Road in Malvern, where policy supports more intensive forms of development but development is constrained by the presence of numerous single dwelling covenants. Presently, an application for planning permit for a medium density housing would likely fail if it was opposed by beneficiaries of the single dwelling covenants, but subject to satisyfing questions of neighbourhood character, that may be about to change.

The new laws may not come into effect until 2028, assuming they pass both houses of the Victorian Parliament without significant amendments.

A more detailed analysis of the Bill can be found here in the consolidated notes, under ‘Attempts at Reform’.

[1] Fitt & Anor v Luxury Development Pty Ltd [2000] VSC 258.

The Supreme Court will generally discharge covenants that fail to identify benefiting land without notice

The Court is routinely invited to declare restrictive covenants unenforceable on the grounds that no land is identified as benefiting from a restriction, and it will generally do so without any form of public or private notice:

- in Re Pomroy S ECI 2021 03444 Matthews AsJ (as she then was) discharged a restrictive covenant on the grounds that “The restrictive covenant contained in Instrument of Transfer No. 1159026 in the Register kept by the Registrar of Titles under the Transfer of Land Act 1958 (Vic) is not enforceable by any persons other than the Transferors named in the said Instrument of Transfer”;

- in Re Antony & Sunita S ECI 2023 03873 Ierodiaconou AsJ concluded that the Covenant was invalidly registered, as it “failed to identify any land as taking its benefit”. It followed that: “The Covenant should be discharged because of there being no substantial injury to any person entitled to its benefit”; and

- in Re Burton S ECI 2024 02915, Daly AsJ discharged a restrictive covenant on the grounds that “The Court is satisfied that the covenant is invalidly registered, as it fails to identify any land as taking its benefit. The covenant should be discharged because of there being no substantial injury to any person entitled to its benefit.”

No form of notice was required in any of these applications.

A vivid example of why you should not apply to VCAT to modify or discharge a covenant

In Mirams v Boroondara CC [2022] VCAT 928, the Tribunal considered an application for planning permit to remove a restrictive covenant from a title to land in the Grace Park Estate. Following the provision of notice, a practice day hearing was held, followed by a preliminary hearing at which the permit applicant was represented by a QC, Council and three objectors were represented by solicitors and two parties were represented by lay advocates.

In contrast, a similar application was considered by the Supreme Court in Re Moolman in S ECI 2025 4277. No notice was required and the Court determined the application after brief submissions from counsel.

The wording of the covenants were in all relevant respects identical and the effect similar, namely the discharge of the covenants, but the VCAT proceedings took months and attracted considerable attention, whereas the Supreme Court granted the relief sought without notice and in the space of three weeks from commencement of the application.

Another building materials covenant amended without notice to beneficiaries

The Supreme Court has again amended a building materials covenant without requiring notice to beneficiaries. This is appropriate because rarely do beneficiaries object when notice is given of such an application. In this case (as with others), no expert evidence was required and the orders were granted in about three weeks from the application being made. See Re: Besser S ECI 2025 4337.

How to protect against a future purchaser attempting to renegotiate a settled agreement to modify a covenant

To the best of my knowledge there is no settled authority on the question of whether a negotiated agreement to amend a covenant becomes the new comparator or floor, for the determination of substantial injury in section 84(1)(c).

This is of particular significance to parties negotiating an amendment to a covenant prior to the land being sold. In practical terms, beneficiaries are entitled to ask: “what’s to stop the purchaser having another go at this, but using the negotiated agreement as the basis for determining substantial injury under section 84(1)(c) of the Property Law Act 1958?”

This challenge was met with the inclusion of the following words in paragraph H of other matters in Re Natwes in the draft consent terms provided for the court’s consideration: “In compromising the proceeding, the parties agree that the modifications set out in this order (Agreed Modifications) will not result in substantial injury but acknowledge that any further modification, however minor, may result in a substantial injury to the beneficiaries having regard to the protections afforded by the Covenants in their original form.”

Should you apply to modify a covenant via the planning permit process if s60(2) of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 applies?

For covenants created on or after 25 June 1991, applicants are often tempted to pursue the modification of covenants through the Planning and Environment Act permit application process on the basis that it is purportedly cheaper than applying through the Supreme Court.

However, this can be a false economy when considering that each beneficiary needs to be notified via the Planning and Environment Act 1987 process and depending on the size of the subdivision that can be expensive. I have had clients complaining that the process of notice can cost $3,000 for small to medium subdivisions to $10,000 for larger subdivisions.

Moreover, the obligations for the production of evidence are no lower in the Tribunal and so the cost of engaging an expert may be greater given that the expert will invariably be required to appear to give evidence at VCAT, whereas a judicial registrar or Associate Judge will typically be content to consider the evidence on the papers.

And that hints at perhaps the critical distinction—that cases in VCAT are more often than not opposed by beneficiaries who bear few if any cost consequences from appearing to oppose an application to modify a restrictive covenant, whereas in the Supreme Court applications to modify restrictive covenants are more often than not, unopposed.

Moreover, Council as the responsible authority will invariably be a party to an application for planning permission, whereas they will only rarely be involved in a section 84 application, for instance, if Council owns nearby parkland that enjoys the benefit of the covenant sought to be modified. Taking that wildcard out the equation alone is of profound assistance to applicants.

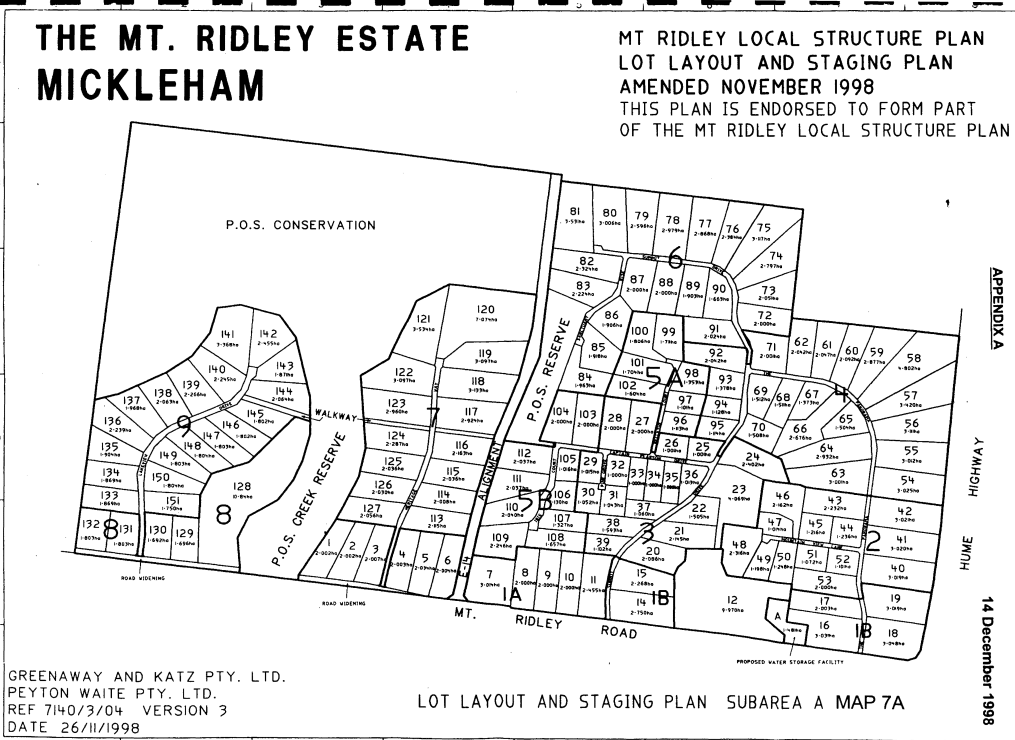

The test in section 60(2) of the Planning and Environment Act can also be more narrowly applied than section 84 in the Property Law Act. By way of example, in Ambrosio v Hume CC [2019] VCAT 2049 the Tribunal rejected an application for an additional dwelling at 30 Eucalyptus Ct, Mickleham in the Mt Ridley Estate, whereas the Supreme Court has since approved seven somewhat similar applications in the same precinct.

The network of covenants in the Woodlands Estate, Mt Eliza may be broken

Lots in LP 40704, shown below, have for many years been believed to be the subject of a network of single dwelling restrictive covenants.

The integrity of this network has recently been drawn into question by three decisions of the Supreme Court of Victoria either modifying the single dwelling covenant to allow a second dwelling on the lot, or discharging the covenant completely.

The process for modifying or removing the restrictive covenant on your land might adopt the following course:

- receipt of advice to confirm that your covenant has similar features to the other applications;

- the drafting of an Originating Motion to the Supreme Court of Victoria to remove the covenant or modifying it to allow one additional dwelling;

- the giving of notice of the application, which may consist of putting a sign on the land for four weeks; and

- upon the consideration of any objections, relief being granted in terms similar to those sought, namely the discharge or modification of the covenant.

In the most recent applications, planning evidence has not been required.

Upon the granting of the relief by the Supreme Court, a planning permit might still be required to subdivide your land to create an additional lot for sale, but it would likely be no longer barred by s61(4) of the Planning and Environment Act 1987.

Some exemptions from planning laws might apply, for instance, for the construction of a small second dwelling.

The Supreme Court makes a further modification to the covenants in the Mt Ridley Estate in Mickleham

On 17 June 2025, in Re Kaur S ECI 2025 01364 the Supreme Court made a further modification to the network of restrictive covenants in the Mt Ridley Estate, Mickleham, shown below:

That takes the number of titles modified to allow an additional one or two dwellings, to six or more in recent years. We are now finding that most applications proceed unopposed.

And for good reason. Large subdivisions of land such as that in the Mt Ridley Estate incorporate single dwelling covenants often as an assurance to planning authorities that infrastructure will not be overwhelmed by the subdivision and subsequent development of land.

As time passes, and surrounding land is intensively developed, these subdivisions stand as artefacts to infrastructure conditions long gone.

Lots remain sufficiently large for further subdivision to occur without noticeably impacting on the amenity of neighbouring beneficiaries and the Supreme Court seems increasingly comfortable in approving applications to vary these covenants.

Significantly, the experience has been quite different for those people who apply via the permit application process, with an application in Ambrosio v Hume CC [2019] VCAT 2049 being refused on the basis that the grant of a permit could result in amenity or character loss through the creation of a differently shaped lot.

The Supreme Court, however, has been flexible in the creation of regular lots and battle axe allotments to work around existing dwellings.